Studio Ghibli and Modernity

Preamble

This is the first article of the series, Studio Ghibli as a section of Japan and Modernity, which aims to examine Japan’s experience of modernity through the critical analysis of Studio Ghibli’s feature films. It is a part of an effort to articulate Japan’s experience of modernity through the exposition of select Japanese animated films, and thus this set of essays is followed by another series which focuses on other select post-WWII Japanese animated films. Whilst there are many auteurs with distinct styles and philosophy in this crowded field, Studio Ghibli is given a separate series due to their significant contributions to Japanese culture and its special standing as the pioneer of animated cinema that is capable of aesthetic sophistication and philosophical depth. Their founders, Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki, have successfully challenged the perception that animated films are mere entertainment for children and transformed the way in which animated films are crafted. The shift initiated by them has altered the perception of animated films amongst the general audience. Studio Ghibli set against the model embraced by the likes of Disney Studio and Dreamworks: they have proven that animated films are capable of producing great artistic achievement and must be considered equal to live-action films on merit. Whilst there have been many distinguished figures in Japanese animated films, none has been able to match Studio Ghibli in its prolificness, inventiveness and cultural impact for over three decades during which they have demonstrated a remarkable consistency: neither Takahata nor Miyazaki has produced a single weak film for Ghibli. From the moment Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Grave of the Fireflies screened, these maestros have dominated the Japanese cultural scene: every new release of Studio Ghibli has become a national event and their respective ’swan songs’, i.e., The Wind Rises and The Tale of Princess Kaguya, confirmed their creative longevity. However, the consistently high quality and inventiveness alone do not explain their special place in the history of animated films: the likes of Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell, The Sky Crowlers) and Satoshi Kon (Perfect Blue and Paprika) have exerted transformative influences upon popular culture at home and abroad, yet they have not directly challenged the standard set by the likes of Disney: since their work unreservedly embrace the subject and the aesthetics which many find unsettling, they cannot change the general perception of what animated films can accomplish. The unique standing of Studio Ghibli in Japan and abroad owes to the accessibility of their work. Despite the challenging subjects such as children in war and the philosophical contemplation on the nature of modern civilisation, their work has always been accessible to a wide range of audiences. The Ghibli features provide a rare opportunity for an entire family to sit together for two hours and share an extraordinary experience. Hence, no cultural theory upon post-WWII Japan is complete without a dedicated analysis of their work. And thus, in what follows, I wish to offer an overview of the differing attitudes toward modernity expressed through the work of Studio Ghibli.

Experiencing Modernity

‘Modernity’ is a familiar concept. When someone or something is described as ‘modern’, it generally means: being innovative, sleek, and free of unnecessary constraints from the past. Whilst the notion of ‘modern’ now appears as a matter of perception and thus is subjected to marketing and PR, it derives its meaning from a specific historical development in Europe: modernity represents the notion of progress fostered by the humanistic tradition which saw its inception in the Renaissance period and transformed the European Form of Life during the Early Modern period. Whilst it is not entirely secular, the Geist of modernity is humanistic, that is, it places the faith in the human capacity to improve themselves and the world they inhabit by the power of human reason and science. This broad movement has opened the possibility for revolutions, be they political, scientific, aesthetic or philosophical. This lofty intellectual development was initially assisted by technical advancement: the invention of the printing press broke the ecclesiastical monopoly of the knowledge that underpinned the foundation of European society and helped intellectual dissent from the states and the church. The seismic intellectual shift did not come without struggles: many Enlightenment thinkers and philosophers risked their lives in pursuit of intellectual freedom. Despite the state and ecclesiastical oppression, this movement grew in its influence and developed into the Age of Enlightenment, or Early Modern period of history. It was in this period when seminal documents such as the Declaration of Human Rights and the American Constitution were drafted, adopted and presented the case for the scientific world-view and the core principles of a modern democratic republic. Whilst these documents and the philosophy that supported them were by no means flawless, they inspired the concept of civil society in which one may enjoy justice, equality and civil liberty. Yet, this development coincided with the births of various nation-states in Europe whose territorial and economic ambitions demanded the technical advancement of navigation, transportation, industrial production and weaponry. Since material inventions outpaced the implement of philosophical development due to the slow process of political reinventions, the purely technical aspect of modernity enjoyed the head-start and steered the course of modern history toward Imperialism. That being acknowledged, the lofty and humanistic ideal of philosophers and political thinkers did not simply disappear: instead, the tension caused by the contradictions between philosophical modernity and the industrially materialist drive for domination intensified. Some philosophers and politicians attempted to rationalise the discrepancy between theory and praxis by resorting to a hypocritical duality: for instance, John Stewart Mill argued that the humanistic concerns for equal rights and welfare only applied to European masters; colonial subjects for him were not ‘fit’ for such considerations due to their alien Forms of Life. Whilst the Briton insisted that he saw no inconsistency in such a duality, and thus pioneering cultural relativism of an imperialist kind, the philosopher should have known just how untenable his position was. The hypocrisy such as this not only undermines the credibility of the Enlightenment as a humanistic movement; it signifies its submission to the brute force of Industrial Materialism.

It is important to note that the hypocritical rationalisation of this duality only represents the ‘Western’ experience of modernity. As Mill asserted, non-Europeans were not the subject of humanistic concerns in the eyes of Europeans and colonial settlers, and thus, the experiences of modernity for non-colonialists have been fundamentally different from that of Europeans. In addition, although I think that the conflicted nature of ‘non-Western’ experience of modernity described about Japanese experience in my articlegenerally applies to other non-European experiences of modernity, to understand the modern experience of a specific Form of Life, we must consider the concrete historical context that is unique to the region in question. For instance, whilst sub-Saharan Africans suffered a historic horror of human trafficking and slavery in addition to colonisation, others did not become the subject of the slave trade on a comparable scale, and thus sub-Saharan African experience of modernity has been fundamentally different from others’. Whilst the Japanese traded women from Japan, China, and Korea for European firearms, it was of a diminutive scale relative to what sub-Saharan Africans suffered. As a result, the terms such as ‘slavery’ and ‘racism’ do not invoke the historic pain suffered by sub-Saharan Africans and their descendants in places like Japan. Such differences in respective experiences of modernity have had fundamentally shaped their views on modernity and informed their reactions to it. In addition, the method of domination and exploitation varied greatly by region. For example, despite the enormous pressure from France and Britain, Thailand maintained independence whilst neighbouring Myanmar was colonised by the British as the result of the Anglo-Burmese Wars during the 19th Century. And thus, it is important to note the sheer diversity regarding the experiences of modernity, which are specific to regions. Therefore, we should not be surprised to see some Forms of Life demonstrate strong resistances to modern influence, as others express conflicting interests or open appreciations of it. Furthermore, a historical context which determines the experience of modernity is not merely topological; it is also temporal. The experience of modernity in a specific region greatly differs from one generation to another. For instance, the experience of imperialism in Myanmar differs between generations: British colonial oppression was experienced differently from the ones who faced direct military aggression to the ones who came after the colonial wars. Hence, we need to carefully consider the specificity of historical experience before analysing what modernity means to a given population. In regard to the present inquiry, this means that ‘modernity’ for the auteurs of Studio Ghibli is specific to their experience of it. And thus, in what follows, I wish to unpack the concept of modernity according to their unique historical experience.

The Children of War

In order to grasp what modernity means for the auteurs of Studio Ghibli, we need to situate the concept within a specific historical context wherein these filmmakers experienced it. Whilst it is important to recognise the generational differences between the founders of Studio Ghibli and the younger directors regarding their respective experience of modernity that inform their world-views and creative decisions, it cannot be denied that its revered founders have exerted dominant influences over the younger generations of animated film directors in Japan. Studio Ghibli’s legacy belongs to its founders, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, and thus I shall outline their respective attitude toward modernity in this essay and reserve the detailed comments on the perspectives of the younger generation of Ghibli directors as I analyse individual films directed by them. Hence, before probing the respective differences between two legendary directors’ views on modernity and their individual responses to it, I wish to outline the shared historical context from which they emerged.

Studio Ghibli was founded by two legendary filmmakers, Hayao Miyazaki (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away), Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, Only Yesterday, The Tale of Princess Kaguya), and the producer Toshio Suzuki in 1985. The studio was established in the wake of the groundbreaking success of Miyazaki’s first distinct feature film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which was released in 1984. It was based on the seven-volume epic graphic novel by Miyazaki, who created it as a pretext for the feature film on Nausicaä’s story. It was hailed as a historic achievement by critics. The story of a brave heroine caught in the middle of tribal conflicts in the post-apocalyptic world captured the imagination of the audience and became a major cultural phenomenon in Japan. It has been consistently regarded as one of the best animated films of all time and practically determined Miyazaki’s creative direction. The film was a financial success for Miyazaki and his team, in which both Suzuki and Takahata served as producers: it topped the box-office in Japan with the total of 1.48 billion yen and prompted Suzuki and Miyazaki to form an independent animated film studio and production company. Miyazaki was motivated to take this risk due to his concerns over the sustainability of high-quality animated cinema and the welfare of animators: because Nausicaä demanded an extensive work by each and every animator involved, Miyazaki was alarmed by the gross imbalance between the hours animators put for the work and the pay they received through their respective contracts. In order to produce higher quality films, then, Miyazaki convinced Suzuki to create their own company to hire skilled animators and protect their financial security and well-being as their employees. Once the duo agreed upon the plan, Miyazaki asked his long-time mentor and colleague, Isao Takahata, to join the company. These moves by Miyazaki were consistent with his early career: when he was working for Tōei Animation, one of the major production companies in Japan, he led the collective bargain during a major labour dispute as the chief secretary of the Union in 1964 under the guidance of his mentor, Isao Takahata, who had already begun to advance his vision of animated films as an established assistant director.

Despite the difference in their respective creative visions, they held one another in high regard and collaborated extensively at Tōei Animation. Whilst Takahata acted as a mentor due to his revolutionary vision of animated films and his intellectual gift, Takahata saw a rare creative talent in his younger colleague. As we shall analyse their individual experience of modernity and the resulting creative differences, it is necessary to note their shared experience as contemporaries. Whilst Takahata’s admiration for Italian Neo-Realists such as Rossellini and French Nouvelle Vague was well-known, there was one experience defined his generation: they belonged to the only generation who experienced the WWII as children and remembered Japan before the war began. Miyazaki tells us that Takahata’s experience of the US air raid of Okayama City and the subsequent struggles for survival at the age of nine defined Takahata’s world (The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness). Much like the protagonist of his first Ghibli feature, Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata and his family were the victims of the US air raid. Having separated from his family, he wondered in the wasteland in search of his family for two weeks without shelter or assistance. According to Miyazaki, no one offered a single glass of water or food to this starving nine-year-old, and he concludes that the hostility Takahata faced in the ground zero caused irreparable damage to his personality. Whilst Miyazaki does not elaborate what he means by his statement upon Takahata’s character, it is clear that the experiencing the WWII as a helpless child has shaped Takahata’s world-view and has strongly informed his creative decisions. Whilst one might think of Miyazaki’s statement about his long-time collaborator slightly presumptuous, if anyone was going to offer an insight into the psyche of this reclusive enigma, it had to be Miyazaki: not only because they have worked closely for decades, Miyazaki understood Takahata’s experience as another child of war; he survived the US air-raid when he was four-years-old and has openly acknowledged the lasting impact of the bombing. And thus, both directors are children of war whose childhood were shattered as they were subjected to the absurdity of indiscriminate violence which was exercised unreservedly and bidirectionally. Both directors occasionally voiced their commitment to pacifism and defended the Article 9 of the post-WWII Japanese constitution, which interpreted the notion of ‘self-defence’ strictly and categorically prohibited Japan from engaging with military actions abroad. When the government led by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe amended the said article of the Japanese constitution, both expressed their strong oppositions. Miyazaki, in particular, published a full-page op-ed which strongly condemned the younger generations’ disregard of Japan’s ‘arrogant and immoral’ actions during WWII. It is also notable in the context of the present project that both Miyazaki and Takahata experienced the 1960s, the period of exponential economic growth and student protests, as professionals, not students, and this generational experience could explain one of the unique characteristics of Ghibli films: whilst their work has had a formative influence over Japan’s popular culture, their creators stayed above the ebbs and the flows of cultural trends as their inspirations originated from earlier times in the 20th century. They shared a strong antipathy toward the consumer society emerged from the rubble of WWII. Whilst they did not embrace dialectical materialism of the student protest movement from the 1960s and the 1970s, having spent their entire childhood in the pre-WWII Japan, they grew critical of Japan’s ‘present and future’ as much as their Imperial ‘past’. That being acknowledged, it is also important to note the remembrance of their respective childhood before the violence of war that transformed their lives serves as reference points from which they critic the ills of post-WWII Japanese society. Due to this cultural memory, neither Miyazaki nor Takahata fell for the abstraction of political ideologies: they had respective concrete visions wherein life was wholesomely enchanting. Therefore, the creative endeavours of these directors, as a team and as individuals, must be understood as a struggle not to come to terms with the loss of childhood and to prevent such a loss from happening again. That being the case, as their public disagreement about their respective artistic choices and their underlying divergence regarding their respective world-view demonstrate, their reactions to modernity differ considerably. Whilst I shall reserve a detailed analysis of the ways in which these differences manifest in their individual films in the following articles, I shall close this essay by outlining their respective response to modernity.

Magic and Loss I: Takahata

Isao Takahata was born in 1935. His father was a junior high school principal, who later became the education chief of Okayama prefecture in Western Japan. Takahata and his family survived a major air raid on Okayama City in 1945, which fundamentally altered his nascent world-view. After the war, he majored in French Literature at Tokyo University. He was influenced by French Nouvelle Vague and Italian Neo-Realism. In early 1962, Takahata applied for a position in Tōei Animation, one of the major animated film production studios in Japan, and began to work for television shows and feature films. During this period, Takahata began to research the novel methods and techniques specific for animated films. He was the first to realise that one could not simply adopt the method of live-action films to animated films, and thus he has been deservedly credited for re-inventing animated films in Japan. He is also known for his painstaking naturalism. Takahata pioneered a rigorous attitude toward every detail of the scenes, thereby enabling animated films to tackle serious issues in everyday life, as opposed to mere entertainment for children. Takahata was also unique in the world of animated cinema: he has enjoyed the distinction of the only major animated film director who did not begin his career as an animator. He was primarily interested in animated film as a medium of aesthetic and philosophical expression, despite the fact that he singlehandedly revolutionised the medium by critically reevaluating every technical aspect of it. Not surprisingly, Takahata was well ahead of his time: Takahata’s approach to the animated film was critically lauded without producing a tangible box-office success. The lack of financial reward strained his relation with Tōei, and following the poor box-office of his first feature film, The Great Adventure of Horus, the Prince of the Sun (1968), which he directed and Miyazaki served as the key animator, Takahata was blamed for the failure and demoted. Incidentally, the ‘failure’ of Horus summarises the trajectory of Takahata’s long career: his vision of animated film had often been misunderstood, and his feature films were received with perplexity at times, only to be hailed as groundbreaking endeavours later. This was precisely the case for Horus: it is now considered the first defining Japanese animated film, yet none presaged its place within the canon at the time of release. Having been sidelined within the company, Takahata and Miyazaki left the studio and became free-lance directors. Throughout the 1970s, they continued their collaborations as a unit until the aforementioned success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind enabled them to establish their studio. That being the case, their creative difference has been well-documented: Miyazaki’s frustration with Takahata’s often seemingly intangible efforts was at times publicly expressed. Over the years, as Miyazaki released one epoch-defining film after another and became the representative figure of Japanese animated film, Takahata appeared to be content to occupy a small esoteric niche under his younger colleague’s shadow. Whilst his output was no match to his industrious peer, this perception, while common, is inaccurate. As we shall see later, Takahata’s perplexing experiments would be often successfully adopted by Miyazaki’s masterpieces that followed. Whilst the specifics of their creative exchange will be further analysed in later articles, it is important to note that the tension existing between Takahata and Miyazaki ultimately benefited the entire studio as a creative unit. This creative exchange was possible due to their shared historical experience: whilst their reaction to the modern world may be sharply contrasting, they had shared common experience as children of war who found themselves alienated from the post-WWII Japan as they became the vanguards of the very culture from which they felt estranged. Thus, the ways in which they reacted to their shared experience of modernity were generationally distinct.

Whilst Miyazaki is known as the wizard of fantasy cinema, Takahata has been credited with the introduction of Realism in animated film. He is widely admired for his successful effort to direct animation films which are capable of dealing with everyday reality and the important issues of the past and the present. The subject matters of his work are serious and critical, e.g., children at war, the destruction of rural community, the loss of habitat for wild animals in Japan, to name a few. Takahata’s effort was unique in that, unlike Miyazaki who aimed to inspire the audience by questioning the existing Form of Life through epic fantasy films and engaged the audience with lofty philosophical discussions, Takahata wanted to examine a specific social problem directly and advocated for a certain strategy or a possible solution in order to overcome it. For Takahata, the source of ills in modern Japan was found in the consumerism and monetarism resulting from Japan’s cold-blooded drive to rebuild the nation in its pursuit of material wealth: he thought that the civilisation founded upon Liberal Capitalism rendered life disenchanting. Takahata found the prime example of this symptom in a comfortable yet empty life in a metropolitan city such as Tokyo. For Takahata, in order to reclaim the lost magic in the mundane realities of life, one must seek a place in a diminishing rural community where life could be still wholesome; in such a community, one must feel the interconnectedness of human activities and the natural environment. In short, Takahata wanted his work to show the way in which we could fundamentally rethink our civilisation as a whole. Thus, Takahata largely shunned creating fantasy dramas and insisted on dealing with important issues of life in contemporary Japan through stories that were rooted in everyday life.

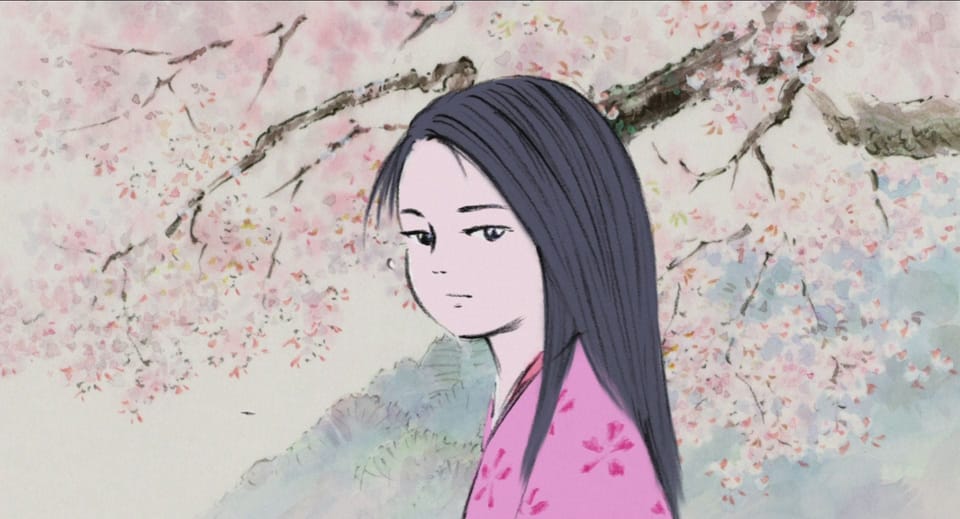

Yet, there is another aspect of Takahata’s Realism which has been overlooked. Whilst his political engagement has been well-documented, his cinematic Realism is not merely about his groundbreaking technical and theoretical contributions that have redefined what animated cinema could accomplish as a medium: his rejection of fantasy films as escapism is not as much as his commitment to deliver a sociopolitical message to the audience; it is more to do with his desire to open our eyes to the enchantment of ordinary moments. This is evident in every film Takahata has directed. Even in the film with a bleak subject such as Grave of the Fireflies, there are moments of unexpected flight of imaginations and the simple joy of life that enchant us. Whilst Takahata’s political engagement is serious, this aspect of his Realism prevents his work from becoming didactic. It must also be noted that the philosophical aspect of his attitude toward modernity underlies Takahata’s Realism: like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Takahata sees civilisation as the source of ills and disenchantment of life. Whilst his political polemics are often central to his films, his Rouseauesque attitude toward civilisation is pervasive: he favours rural life over urban one, and he views childhood as the untainted state of innocence. In his later career, for the reasons I shall discuss in the analysis of individual films later, Takahata began to express himself less politically and more poetically. To the perplexity of many and the exasperations within the studio, in creating his last work of the 20th century, My Neighbours the Yamadas, Takahata once again radically broke from conventions and released a full-length feature film with neither a fully animated cell nor a linear storyline: it is a loosely assembled slice of life from a certain period of the post-WWII Japan. Whilst the mundane represented in the film bears the strong resemblance to the idealised version of the 1950s, unlike the popular TV animation series called Sazae-san based on the comic series by Machiko Hasegawa, Takahata neither follows the conventional storytelling which takes the harmony within a family life granted nor modern animation techniques. This aesthetic experiment was so revolutionary in that the full extent of Takahata’s invention was not fully in our view until the release of his last film, The Tale of Princess Kaguya. In these last two feature films, Takahata broke from the technique he helped perfect for Studio Ghibli and produced feature films made of ethereal watercolour. In his final stage of life, Takahata revealed himself as a haiku poet who cherished the magic of ordinary moments in life. Still, despite his retreat from a specific political view or another, as we can see in the story of Princess Kaguya, his attitude toward modernity remains consistent: he rejects the urban life in favour of rural life which offers some chance to rediscover the enchantment in the mundane. Takahata insists that the complications that brought about by human civilisation must be rejected, and modernity is the force that annihilates the enchantment of life and renders it meaningless.

Magic and Loss II: Miyazaki

Whilst Takahata took a consistent attitude toward modernity, it was more complicated for Miyazaki. This is due to his specific upbringing and childhood experience. Hayao Miyazaki was born in 1941 in Tokyo. His father was the director of Miyazaki Aeroplane, the manufacturer of the rudders for fighter planes during WWII. Due to the intensifying firebombing of Tokyo, the family moved to Utsunomiya City when he was three. Like Takahata, Miyazaki and his family survived the major US air raid there when he was four-years-old, and he later recounted the ‘lasting impression’ from this experience. It is not difficult to see how the hallowing brush with death and witnessing the indiscriminate destruction of civilian life with the use of modern technology had shaped Miyazaki’s view of modernity. That being noted, for Miyazaki, modernity did not only represent the destruction of life: it also enchanted him. Whilst Miyazaki had a first-hand experience of its destructive capacity as a young child, he was also fascinated by the wonderment of modern technology represented by airplanes, the technology his own father was involved and also nearly killed him. On one hand, modern technology was the harbinger of death. The indiscriminate destruction of carpet bombing targeting the civilian population living in the flammable houses made of wood was ruthlessly carried out by the US Air Force as their retribution. The scorched earth policy, which Robert McNamara later deemed a war crime, was made possible by the advanced aviation engineering and the mass production capacity of the American aviation industry: the fleets of B-29 carried out the waves of carpet bombing, unchallenged from the altitude where Japanese fighter planes and interceptors could not reach. At the same time, Miyazaki has been fascinated by the flying machines, including military ones, the infatuation that was inevitable for someone whose father made a living within the Japanese aviation industry during the war. Not only his father’s position in the war industry guaranteed the relative affluence during and the after WWII, but the child’s curiosity was also intensely directed toward aviation. This unique upbringing added a certain complexity to Miyazaki’s experience of modernity: he has been forced to grapple with its wonderment and its destructive capacity for his entire adult life. For Miyazaki, modernity is a double-edged sword that is at once the source of magic and its leaper. As we shall see later in the analysis of individual films by Miyazaki, this ambivalence toward modernity becomes the major theme throughout his illustrious career.

Miyazaki later majored in political science and economics at Gakushūin University and took part in the Children’s Literature Research Club, which exposed him to the work of many authors which he later adapted into feature films. Upon graduating from the university in 1963, Miyazaki was employed by Tōei Animation Studio as an animator and began to work with Isao Takahata. Soon after the employment, Miyazaki played a central role in the labour dispute at Tōei Animation and became the chief secretary of Tōei Labour Union in 1964. Whilst Miyazaki grew increasingly critical of the role of technology and engineering in war, and he confronted his father for his role in the war effort of Imperial Japan, whose colonial ambition he condemned as arrogant and immoral, he was unable to divorce himself from the enduring fascination with the wonderment of technology despite his pacifism. This attitude endures despite some notable changes evident in his later work. Modernity is not merely the source of malady for Miyazaki: it is also the subject of childlike fascination. This ambivalence toward modernity is central to Miyazaki’s cinema and repeatedly expressed in all of his epic films such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke and The Wind Rises. As he is preoccupied with his concerns over the environmental destruction through industrialisation and the use of technology in war, he does not condemn modern civilisation in its entirety as Takahata did. Instead, Miyazaki has sought to argue for the mindful use of technology that ensures the balance between human civilisation and the conservation of the natural environment. Whilst his message has been received empathically, it is notable that his epics have been fantasy films. Even The Wind Rises, the story about the designer of Mitsubishi A6M, AKA ‘Zero’, is a poignant fantasy about the magic and loss: a young aviation engineer’s struggle to create something ‘beautiful’ at the centre of Imperial Japan’s war effort. As this ‘swan song’ demonstrates, for Miyazaki, the ambivalence toward modernity is experienced at a deeply personal level. Despite his sociopolitical engagement, he has never committed to one particular political direction or another. Whilst he led the major labour dispute in the film industry during the 1960s, he has never theorised one concrete solution or another: he has preferred to engage philosophically rather than politically with the contradiction of modernity, that is, its wonderment and its destructive power. And thus, whilst he shares with Takahata a strong affection for children’s capacity to experience the magic of life, he does not see adulthood and civilisation itself as the downfall. As an artist, he has not been concerned with suggesting some concrete solutions and remedies that correct the ills of modernity. He has been focused on inspiring the audience to see his view on modernity and the role of humanity in the world by bringing back the enchantment of life on the screen. Another reason for Miyazaki’s creative choice is based on his consideration for his targeted audience. Whilst Takahata was credited for pushing the creative boundaries and reinventing the medium, Miyazaki has established Studio Ghibli as a trusted brand, a strong alternative to the likes of Disney. Whilst Miyazaki has injected creative innovation and thoughtful storylines to his work, and thus elevating the medium, he has mostly stayed within the boundary of what is considered appropriate as family entertainment. Whilst Miyazaki’s creative direction has defined Studio Ghibli as a brand, it has also limited Miyazaki’s engagement with modernity: he would inspire the audience to think about the place and the role of humanity in the world without suggesting any possible paths to follow. Whilst Takahata would unflinchingly describe the horror of war in Grave of the Fireflies, Miyazaki would engage with the same subject as abstraction, as we see in Howl’s Moving Castle: there are no burnt human remains present on Miyazaki’s screen. Whilst this choice is neither better nor worse relative to Takahata’s in and of itself, it does mark a stark difference between the two most distinct auteurs of Japanese animated cinema.

How Do We Live Now

Despite the aforementioned difference, Takahata and Miyazaki have been asking the audience the same question: How do we live now? Whilst their respective world-views and creative decisions may differ greatly, they share the same Geist as contemporaries who survived the most brutal war in human history as helpless children. The violence that shuttered their childhood and the subsequent development in which they participated as adults yet from which they were alienated defined their experience of modernity and informed their creative directions. Having lived through the devastating hardship of war and its trying aftermath, the society which single-mindedly focused on future development without reflecting upon the meaning of the recent past deeply unsettled their generation. On one hand, they worried that the history might repeat itself without the proper atonement for the wrongs and the crimes Japan had committed during the war. On the other, they began to see the unintended consequences of industrialisation as adults. Whether it was environmental destructions or the loss of enchantment in life materialised in the mindless pursuit of material wealth, they were concerned with the question of how to live meaningfully in the post-WWII Japan. Notwithstanding the fact that their differences were never resolved, as Takahata once noted, they regarded one another as comrades who were fighting for the same cause. In the next article, I shall examine their first major collaboration which established itself immediately as the landmark achievement of Japanese animated cinema, that is, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.