Minor Literature

Whilst I think the most of my readers have known already, perhaps I should be clear about the circumstances wherein I operate: I am a ‘minor writer’, the notion first coined by Deleuze-Guattari in their thesis: Kafka: Toward A Minor Literature. I am a Japanese expatriate who has been living in the English-speaking world for more than two decades, and, although I retain everyday-command of the Japanese language, I lost my ability to write anything that meets the literary standard with it. I have been thinking and dreaming in English for the most of my life in this foreign land, yet I have no illusion regarding my attainable command of this alien tongue. Furthermore, I cannot write adequately without the help of computer programs, which are all equipped with some form of artificial intelligence, and I was told that my English bears strange idiosyncrasies. In short, even when my writing is rid of linguistic errors, the way in which it is structured is not native. This is because my thinking is, despite written and spoken in English, not English.

That being acknowledged, my predicament as a minor writer poses mainly challenges that are technical in nature, and thus, I could hardly qualify to be one, since the notion of minor literature illuminates far more perilous implications than what my practical struggles otherwise suggest.

According to Deleuze-Guattari, one is a minor writer if one writes in the language which is not considered one’s native language. Naturally, a language is not only a way in which one engages and negotiates with social norms; first and foremost, it is the way in which thinking becomes possible. If one wishes to have any clearly defined and structured thinking at all, such an activity must result in a clearly defined and structured linguistic form that is possible for us in the given moment. Hence, we continuously and constantly try our best to refine and redefine the use of language. As Wittgenstein showed us in Philosophical Investigations, language, in short, is a Form of Life of which we are trained to become a part.

What, then, would be the implications of living a Form of Life which one does not recognise as one’s own, or worse, which rejects one as the Other?

The problems illustrated by the notion of minor literature can be expressed as the following questions:

1) Who does the considering?

2) What does the notion of nativity entail?

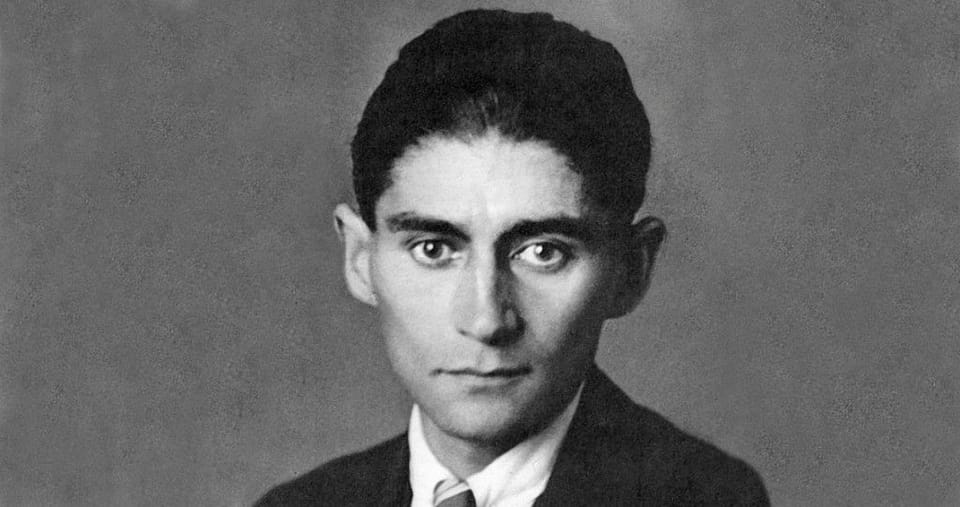

To probe these questions, it was fitting that Deleuze-Guattari turned to Franz Kafka. Their choice to focus on Kafka turned out to be vital for the success of their main thesis; given the fact that Kafka grew up speaking German, and he was not dislocated physically from that Form of Life (he spent little time away from his birthplace, Prague), the tension existed between his keen awareness of the historical context from which he emerged and the Form of Life by which he lived helps us understand what it is to be a minor writer in a uniquely acute and precise way. By turning to Kafka, they were able to show us that the notion of minor literature is not limited to the obvious forms of dislocation, such as migration and diaspora. Since the discrimination and marginalisation are pervasive praxis in all human Forms of Life, and the ways in which these destructive measures are practiced are not always obvious, the relation between the powers that upholds such praxis and the ones who are compelled to subvert them naturally must mirror that complexity.

The condition under which Kafka lived and worked as a writer demands a certain degree of patience on our part to grasp it clearly. Reading and studying Kafka’s work is to break down all recognisable components of alienation, which are quintessential to the modern condition. And thus, despite the historical context wherein Kafka emerged as a writer was specific to the said author, his work touches on critical aspects of the modern condition, either directly or indirectly; hence his being the representative diagnostic case of nearly all Forms of Life that are known to us.

Depending on whom one speaks to, Kafka was an Austrian or a Czech writer, since his birthplace, Prague, changed the status during his life-time, from a provincial Bohemian city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the capital city of Czechoslovakia. He was also a German writer of Jewish origin, although the notion of Kafka being a ‘German’ writer was strictly restricted to the language he used to write.

The instability of his place within the German Form of Life is often explained as a linguistic fact: his German was a particular dialect called Prague German. Due to this fact, some express misgiving to his status as one of the most representative writers of German letters, despite the wide recognition as such. Yet, it is never going to be so simple with Kafka: according to his associates, Kafka’s relation to German language was surprisingly complex. Take his spoken languages, the most immediate and perhaps intimate way in which one relates to given Forms of life. Kafka’s spoken German expressed a heavy Czech accent. His friends noted that Kafka was very fluent in Czech, with which he seemed to have been more comfortable, yet his education was German; hence his written output was all in German, the language he had never felt quite at home. And yet, despite his feeling, Kafka is, technically speaking, indisputably a German writer, albeit only ‘technically’. Note that defining him as a ‘German writer from Bohemia’ does not resolve the tension Kafka had lived through. Whilst he has a secure place in the canon of German literature, he is never going to be a representative figure of German literature in the way in which the likes of Goethe, von Kleist, Hölderlin, Rilke, and Brecht are. As James Baldwin will always be considered first and foremost a great ‘Black writer’ and/or ‘LGBTQ’ writer, and only secondly a great American writer, Kafka is always going to be celebrated as an outsider within German literary canons. Therefore, Kafka was quite right to have felt the acute sense of alienation from the German language upon which he had to depend, and in Prague, his birthplace and the ‘mother with claws’ from which he was never going to escape.

In addition, his Jewishness could not be clearly defined by his own admission. He was neither Zionist nor an Orthodox-Jew. Kafka did not start learning Hebrew until the last years of his life, and, despite receiving bar mitzvah at the age of thirteen, he was never particularly religious: in fact, he identified himself as an atheist as a teenager. Still, he showed keen interest in his Jewish identity: he often referred to Yiddish writers in his notebooks, and he was once close to the leader of Yiddish theatre from Poland. Against the popular perception of this particular language as something to look down, the perception which was dominant amongst German-speaking Jews, particularly amongst Zionists, he even offered a rare public speech to raise awareness of the Yiddish language when he invited the said Yiddish trope to perform in Prague. This unique divergence from the Zionist movement, which was popular amongst his peers, was rooted in his keen historical awareness: he felt alienated from his own Jewish origin, as seen in the work such as Metamorphosis, as a modern secular person.

That sense of separation was not his invention: most Jews in Austria were German speaking, and they fought during the First World War as Austrians. Whilst the notion of ‘assimilation’ of Jews has always been a convenient one for non-Jewish Europeans, in Kafka’s time, Jews opposed Czech rebellions against the Austrian state as Austrians. As such, they also had a dim view of the Yiddish language as well as Zionism (Kafka’s father vetoed his engagement with Julie Wohryzek due to her Zionist beliefs, the fierce opposition that pushed Kafka to write Letter to His Father). This sort of split reaction to the respective Jewishness was observed in the likes of Wittgenstein, one of the most prominent contemporaries of his, who considered himself an Austrian, not a Jew, yet remarked explicitly on his Jewishness at least on one occasion (for English speakers, Culture and Values comes to mind). Still, Kafka is uniquely relentless in his interrogation of his place in a Foreign Form of Life (as Hegel once remarked: self-consciousness is the desire itself; the discursive nature of ours demands self-identification, however erroneously the process all too often unfolds), and he did so outside the preconceived conventions of his time.

He is also one of the most celebrated Jewish writers who was not a Zionist in a way Scholem was, and whose life-long quest was to probe relentlessly the very ambiguity of his own ‘Jewishness’. Therefore, despite his prominence and significance, Jewish perception of Kafka remains ambiguous. I once was told by a specialist of Judaism that the ‘Jews’ I admired, such as Kafka, Spinoza, and Wittgenstein, were all ‘secular’, the notion that implied that their Jewishness was not all that ‘authentic’. Hence, for some Jews at least, Kafka’s Jewishness is considered somewhat suspect.

As if it were not enough for the author to live through such a debilitating complexity and ambiguity, we find his ‘afterlife’ with a peculiar predicament (Forgive us, Herr Kafka, we are not quite done with you yet): if you take a nativist view, then he is perhaps the most prominent Czech writer despite having written in a minor dialect of German, not in Czech. He spent most of his life in his native city, Prague, and he has come to represent the historic city in the way in which, say, Milan Kundera cannot. And yet, perhaps the majority will agree that it is absurd to classify Kafka as a Czech writer.

The condition regarding Kafka’s place in the world described above must be considered at least complex, if not perilously unstable. Whilst it is easy to dismiss Kafka’s popular perception as a solitary, blooding, tormented figure, as Deleuze-Guattari appeared to do in their thesis, it is important to take time to properly reflect on what his suffering, both personally experienced by him and expressed in his work, meant to Kafka. In order to sufficiently grasp Kafka’s modus operandi, and what it means to be a minor writer, making a clear distinction between the personal and literary mode of his alienation is essential, for the first mode concerns his personal experience, and the second mode, which originates from the first, concerns action.

Since there is a good deal of literature regarding Kafka’s alienation, at once social and personal, and his work speaks for his inner struggles itself, I shall refrain from repeating them. It is sufficient for us to note that Kafka seriously considered suicide on more than one occasion. Whilst there is no way for us to adequately understand the depth of his suffering, it is of critical importance for us to respect and appreciate the cost he paid to leave the body of his work. The pervasive problem with Deleuze-Guattari’s sweeping theories, whether they are about the subversive potential of minor literature or the possible resistance against the high-capitalism by reconstituting the concept of ‘schizophrenia’, the thesis inspired by Antonin Artaud, they gleefully glorify their source subjects by stressing one aspect of their work that supports their given thesis and by neglecting their personal human cost. Whilst I am not suggesting that Deleuze-Guattari were ignorant of, or indifferent to, the sufferings of their muses, in their zeal to reinvigorate their heroes’ achievements, they failed to pay proper respect and express the appreciation to their personal pains.

The concern with their failure is: without properly acknowledging the subject’s sufferings, one cannot fully appreciate the fact: what is personal to the author is inseparable from their literary expressions. That being noted, the best literary work, or any work of art, is the result of an uncanny transfiguration of the personal into the aesthetic: hence the measure of the greatness of art, if you will, must be measured by studying how an author confronted, interrogated, the Form of Life which had set the condition for the range of possible existence for them, and how had they managed to subvert that internalised Form of Life by transfiguring it in an aesthetic form.

Whilst Deleuze-Guarrati did marvellously set out the socio-historic condition within which Kafka operated and emphasised the subversive nature of his intellectual and literary activities, they failed to account for the fact that the subject of his interrogation and subversion was highly personalised: it was the fact that Kafka embodied and internalised the Form of Life that rejected him as an outsider, and that he suffered tremendously from it, makes his literary achievement profoundly precious and moving. And the relentlessness of his internal interrogation of the Form of Life by which he lived, and the clarity with which he directed it, and the acuteness with which he endured the pains caused by it, resulted in what we now know as one of the most significant literary achievement of the twentieth century. He achieved this feat by having cultivated his skills in writing and having defined the image of an author as the representative persona of the modern human condition. Kafka, in short, fused the personal and the aesthetic, but at a great personal cost.

Still, despite the glaring flaws, Deleuze-Guattari’s thesis is of seminal importance: at its core, the notion of minor literature points to the ways in which the discriminated and the marginalised may confront, resist, and subvert the Gewalt (Force/Violence) that attempts to degrade them. As Kafka’s example shows, it is not necessary to experience physical dislocation to be a minor writer. As I touched on James Baldwin, one can be marginalised within the Form of Life from which one emerged, and from the language with which one thinks, dreams, and expresses oneself. Speaking like a white intellectual would not have secured Baldwin a seat next to the likes of Mailer and Irving. Despite the quality of his literary output, he would be first and foremost considered a prominent Black writer, a great LGBTQ writer, not a representative American writer. (This is also a personal point for me: speaking perfect American English won’t give me a place in the Form of Life I currently inhabit, hence my lack of interest in any form of assimilation to the said Form of Life.) In a similar vein, Virginia Woolf, despite the critical recognition, would be considered first the great female writer of the twentieth century, not the great British author in the way the male writers of the lesser calibre are considered. Hence, as Kafka starkly illuminated, one can be a minor writer without dislocated physically or linguistically. Every Form of Life contains the violence within it, despite the pretence of civility and tolerance.

Then, the question is: what can one do with the predicament to which one is condemned by being considered as something or other? As the French authors demonstrated through the work of Kafka, there is no need for us to be meekly accepting the blows. We can choose to subvert the internalised Gewalt and transform it into a gigantic vermin, as Kafka did: he took the derogatory German term Ungezierfer, which denoted Jews, to the extreme in order to give a clear form to the violence that shaped the complex map of his tormented existence.

Whilst the subversive act taken by the author did not offer a solace to him from the sufferings he chose to confront, unbeknownst to him, the impact of his work endures. And he has been by no means alone in this relentlessness, partly because many have been inspired by his work to resist and subvert as he did. And, by advancing the concept of Kafka as a champion of minor literature, Deleuze-Guattaari pointed us toward the way of self-recognition and resisting the Gewalt that otherwise would discard us without a trace.

Despite everything, Kafka, for all eternity, defines ‘German’ literature as a representative figure.