Loving Vincent (2017)

Loving Vincent is a love letter whose true recipient has been long gone: a Dutch painter, Vincent Willem Van Gogh, died of infection caused by an untreated gunshot wound, which was inflicted in uncertain circumstances in Auberge-Ravoux, a small village near Paris. Despite unanswered questions regarding what led him to an untimely death at the age of 37, the established story tells us that the ‘mad painter’ (Robert Gulaczyk), who long struggled with the crippling misery of poverty, ill-health, and isolation, pulled the trigger of a revolver and shot himself. Naturally, not everyone is content with the standard theory. The postmaster of Arles, Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd), was a close friend of the painter, and after rereading Van Gogh’s last letter addressed to him, Roulin is simply unable to believe that the Dutchman had taken his own life. Having taken possession of the painter’s recently discovered letter to his brother, Roulin insists that his wayward son, Armand (Douglas Booth), personally deliver it to the grieving sibling. Having been persuaded by his father, Armand reluctantly travels to Paris, only to discover that the rightful recipient of the letter is no more: the painter’s brother, Theo (Cezary Lukaszewicz), died six months after his brother’s death. Undeterred, Armand travels to Auberge, the town wherein the Dutchman worked until his death, to deliver the letter in question to Dr Gachet (Jerome Flynn), who was a close friend and a psychiatric doctor of the painter. By meeting the doctor, Armand also hopes to gain insight regarding the circumstances of his father’s friend’s death.

The rest of the story evolves around Armand’s quest: he transforms himself from a reluctant messenger to a man on a mission to discover the truth about the circumstances of the painter’s demise. In Auberge, Armand encounters locals who share various home-brew-theories regarding the manner in which the painter died. For example, Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), the innkeeper’s daughter whose entire family befriended the painter, has been harbouring suspicions on Dr Gachet based on some strange behaviour on his part, witnessed shortly prior to Van Gogh’s death. A local doctor shared his forensic analysis to Armand that the bullet that wounded Van Gogh could not be fired by the painter himself: he must have been shot by a third party. Then, there is an intrigue of the Dutchman’s rare ‘friendship’ with a young woman, Marguerite Gachet (Saoirse Ronan), Dr Gachet’s withdrawn daughter, who daily brings flowers to the painter’s grave. Whilst Dr Gachet has been the artist’s friend and psychiatrist, it was widely reported that he and the Dutchman had a turbulent fallout right before the fateful incident took place. Yet, despite all the investigations undertaken, as Armand delves deeper into the intrigue, the inquiry reveals more about his interlocutors than the painter himself. Then how could this quasi-detective story, though impressively painted, framed, and directed, emerge as a genuinely moving tribute to Van Gogh’s art and life? The answer to this question is expressed by the title of this cinematic gem: Loving Vincent is really a loving tribute to the life and the spirit of a person whose pursuit of ’truth’ made it impossible to function in the world despite, and because of, his unparalleled inability not to appreciate every aspect of it.

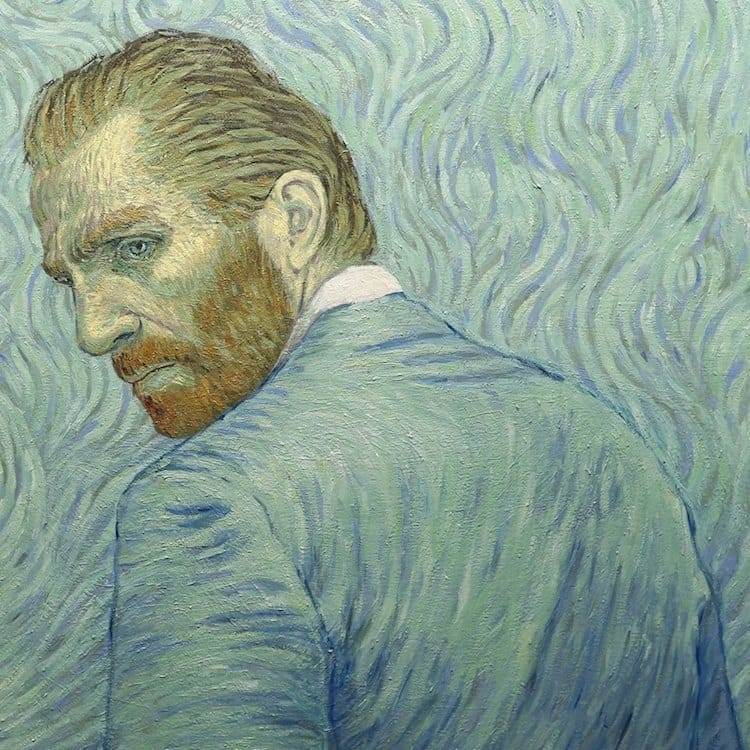

Loving Vincent, the world’s first entirely hand-painted animated feature, is a labour of love by Polish filmmaker, Dorota Kobiela, and a British filmmaker, Hugh Welchman. Originally conceived as a 7-minute short, Kobiela, a painter herself, initially envisioned to paint every frame by her own hand. Yet, as the project turned into a feature length film, the production had to adjust to the scope of the cinema. Eventually, Kobiela and Welchman directed and worked with 125 classically trained painters in total. Each frame is hand-painted in a style of Van Gogh, who inspired various strands of new art such as Expressionism and Fauvism, amongst others, and now hailed as one of the most important catalysts of modern art. To achieve what they envisioned as the world’s first hand-painted film, Kobiela and Welchman settled on an intricate production process: actors are set against a green screen to be situated in a ‘Van Gogh canvas’, and then the painters painted over their impressions by hand, to be incorporated within a ‘picture’. By this unique method, which Welchman called ‘the slowest form of film making ever devised in 120 years’, the directors took four years just to complete the filming and painting. This kind of effort is truly rare in cinematic art. Most productions would not allow such a consuming process, both temporary and financially. The business side of film making simply kills off such an unprecedentedly bold and uncompromisingly deliberate project the moment such a brainstorm begins. Fortunately, some non-profit entities stepped up to support the completion of the project, such as the Polish Film Institute. To sustain and complete a project such as this is a great achievement in itself, yet, quite remarkably, Loving Vincent is not a mere novelty: it is a great cinematic art in its own right that makes us ponder many questions. Whilst the story pulls us into the cinema with a question over the mysterious circumstances of Van Gogh’s death, ultimately, this proves unimportant. Hence, if you expect to have a clear conclusion on the mystery regarding the circumstances of his death, you will be left disappointed. Yet, if that is your reaction to this marvellous film, you are as mistaken as someone who thought Crime and Punishment was a crime fiction.

Loving Vincent is neither a mere dazzling visual affair nor a clever reinterpretation of a biographical detail of Van Gogh’s life: it speaks to us directly about the human struggle of finding a place in this world without betraying oneself, that is, abandoning what one believes to be ‘good’, ‘true’, and ‘beautiful’. Whilst none of us can hope to match the dizzying height Van Gogh attained, he speaks to us candidly and sincerely in his vulnerability: whilst he passionately believed in his vocation, he suffered from crippling self-doubt and lack of validation and understanding. If he was truly a ‘mad man’ who fanatically upholds and imposes ‘his truth’ to the world and crashed with opposition, his life and art would not have moved us in the way it did. He regarded himself as nobody, non-entity, and lowest of the low. He was never enough for his parents, his acquaintances, his ‘fellow’ artists, and above all, for himself. Furthermore, he was afraid that his presence was unpleasant to everybody around him. According to Dr Gachet, his last word to him was that the world would be a better place without him. To his brother, he is said to have uttered: Sadness will last forever. In a letter featured in the film, the would-be painter states: he, a nobody, a loathsome non-entity, nevertheless yearns to someday show what lies in his heart. The letter mentioned was written when he was about to pursue his vocation as a painter; hence it is a statement of intent in a literal sense. It also uncannily anticipated Van Gogh’s future: he never saw that ‘someday’ wherein he could touch people’s heart through his art. Like many great and original contributors to art as broadly construed, the Dutch painter’s work and effort was met with disdain and neglect in his lifetime: it is said that he only sold one painting in his entire life. In short, he was a ‘failure’ by the standard of society, but most critically, everything he did was abysmal in his own eyes.

We must remind ourselves, however: it is not Van Gogh’s suffering in itself that makes him closer to us. It is his genuine and inexplicable yearning to open his heart to the world that speaks to us and moves us profoundly. His pursuit was indeed inexplicable from a worldly perspective. He had no idea how good he would be, or whether he would be able to touch anyone through his art. He did not have a particular method or theory to lead and reshape the world of fine art. There was no prospect of success. He could not find his place amongst fellow artists: everyone dwelled in Paris, and he was unable to stay there. He was neither a child prodigy who demonstrated a sign of exceptional talent, nor someone who set a goal to achieve greatness in one area of life or another. A late starter with no formal training in art, Van Gogh was nonetheless able to transform our perception of art: his ‘style’ was not dictated by formal concerns. For Van Gogh, his canvas was the open window to his soul. There was, literally, nothing to hide. There was no room for pretence and self-importance. It was this singular act of what Levinas might call generosity, coupled with what I consider humility, that separated his art and life from all the rest. Yet, paradoxically, this exceptional soul remains a mystery to us despite his openness. There are so many questions that remain unanswered: Why did Van Gogh choose art?; What did he see as his vocation?; and finally: Why do we practice and value art in the first place? These are the questions for which the painter probably had no answer himself. Whilst Loving Vincent does not pretend to ‘solve’ any of the mysteries surrounding Van Gogh, we must pay tribute to the directors who have made us see what is important, that is, the fact that his life and work matter because of his exceptional openness and sincerity to follow his chosen path against all odds despite crippling despair and insecurity. In this, Kobiela and Welchman achieved a rare feat of directing a cinematic ode that does justice to the legacy of this exceptional person: this cinema helps us understand why his art still matters, and why it is important that it matters. Hence, Loving Vincent in turn proved itself an exceptional work of art on its own merit.