Dead Man (1995), Part III

Introduction

In Part II of this article, we have examined how Jarmusch dismantles Frontier Myth, thereby deconstructing America’s narcissistic collective self-image. Following the opening act of demolishing the idealised notion of the American ‘Frontier’ with a sober representation of a colonial outpost in Part I, Jarmusch exposes the dark shadow of American Geist by creating a double exposure of two cinematic representations of ideal white American men: the quintessential ‘good guy’, Marshall Kane (Gary Cooper) of High Noon on one hand, and Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen), a legendary contract killer who is rumoured to have raped, murdered, and cannibalised his parents, on the other. Whilst Cooper’s lone Marshall is the perennial favourite of prominent law-makers in the United States, Wilson is an incredible embodiment of its shadow, namely nihilism bred by the ethos of Industrial Materialism, which became the dominant feature of American Geist; as extreme as he appears, the killer is, in fact, the logical consequence of the cold-blooded world-view that is perfectly suited for empire-building with its ruthless instrumentalism. Like the mysterious portrait of a vampiric Englishman, Dorian Grey, Wilson serves as a true reflection of the narcissistic collective self-image of American Geist. The stark contrast of the two characters, and the uncanny resemblance between them, are intended to serve as a reminder of the multitude of contradictions made possible by jarring cognitive dissonance existing within American Geist.

Whilst such a critical achievement is significant in and of itself, it is merely half of what Jarmusch accomplishes with this neglected masterpiece; Dead Man is not a mere cultural/historic/political diagnosis of American Geist. Importantly, it also shows a possible way out of, and a way forward from, the great mess that is American Geist. Jarmusch’s sensitivity to the differences between various Forms of Life, and his observation of how they interact, enabled him to explore possible ways for us to break through an initial confrontation, and avoid a stalemate that soon results in discriminations of, and aggressions toward, the Other. In this precise sense, what Jarmusch demonstrates with Dead Man through the friendship between two protagonists is of universal significance. Jarmusch shows: 1) What the prerequisite for creating a possibility for such a friendship is; 2) What the nature of such a friendship is; and 3) The reasons why creating and maintaining the possibility for such a genuine human relation are philosophically significant.

On this note, let us embark on the final part of this voyage.

Fantastic Voyage

In the previous sections, we have examined Jarmusch’s critique of America’s narcissistic self-image by analysing how he demolished it with a sober representation of ‘American Frontier’, and a double-exposure of ideal white men by presenting Cole Wilson as a shadow of the quintessential ‘good guy’, that is, Marshall Kane iconised by Gary Cooper. In this section, I wish to examine another significant aspect of Dead Man: Jarmusch’s concept of possible friendship that offers a way out of the great confusion that is American purgatory. Whilst Dead Man must be appreciated for its potential to transform American Geist by deconstructing the icon of ‘American Frontier’ that justifies colonial violence, it is also a film about an improbable friendship between two misfits on the road, a signature theme of Jarmusch’s early works. That being acknowledged, Dead Man sets itself apart from its predecessors in an important way. This is not only because of this film’s significant contribution to the re-thinking of America’s self-image; the bond between Blake and Nobody is far more significant than that of, say, Willie and Ed (John Lurie and Richard Edson from Stranger Than Paradise). Whilst most human relations in Jarmusch’s work are illuminating, they are situational, that is, entirely by chance, and thus transient. On the other hand, the encounter between Nobody and Blake strikes us as fated. The serious undertone of the cinema is enforced by the context in which our protagonists’ journey takes place. Set against a sinister backdrop of America’s colonial frontline in the midst of ruthless industrialisation during the 19th century, this feature offers a somber undertone, the graveness of which reminds us of Werner Herzog’s masterpiece, Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972). This comparison is not coincidental. One can argue that Henriksen’s cannibalistic assassin is a cinematic reincarnation of Aguirre, Klaus Kinski’s ruthless conquistador; they both embody violent nihilism that renders them extremely dangerous. To think of Aguirre via Wilson as the exact reflection of Marshall Kane in a strictly Wildean sense appears far-fetched at first, yet, upon some reflection, it makes perfect sense: in the context of Americas’ colonisation, the ‘good guy’ who ruthlessly defends his will against the social consent is invented to eclipse the cruelty and the void which lies at the heart of blind aggression. The sole difference is that Europeans do not share the quintessentially American need to claim moral righteousness of their actions; there is no need for the Wildean self-image for Herzog and his audience. In order to dismantle the narcissistic façade that conceals the heart of darkness, Jarmusch needed to introduce Wilson, an American Aguirre, to expose the nature of ‘pioneers’: ruthlessly opportunistic and impossibly amoral, Wilson emerges as a true reflection of an otherwise flawless cinematic icon of an American hero. His entire existence is to prove a point: Nothing matters, and everything is permitted. The celebrated ideal of Frontier Spirit turned out to be an ultimate form of nihilistic survivalism. Such is the darkness that relentlessly hunts down our protagonists to the end, the chronicle of their journey cannot be a typical road movie.

In fact, it does not even fit in a genre which might be called ‘Rogue Movie’. If in doubt, compare Dead Man with classics such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969), or Bonnie and Clyde (Arther Penn, 1967). Whilst Dead Man follows the tradition of 'rogue movies' featuring fugitives running from the law, this is where the similarities end. Despite the ample dose of humour and irony, Dead Man cannot be described as ‘lighthearted’. It is clear that this cinema is not meant to be mere entertainment. Despite their receptions and reputations, the above-mentioned classics are exactly that: entertainment. This means that they make use of existing concepts within a given Form of Life, such as Frontier Myth, to create well-executed stories: Nothing more, nothing less. On the other hand, Dead Man follows cinematic conventions in order to expose the spirit which enables them. With its criticism of Frontier Myth and Industrial Materialism that sanction colonial crimes, Dead Man is a work of great scope and depth, hence a well-deserving comparison with Aguirre. In addition, the voyage of the two protagonists is not merely covering physical distance; it is an educational one for both. According to Nobody, his companion, Blake, is already a dead man. Yet, Nobody accepts a great danger for himself by becoming Blake’s guide through the final leg of the journey, and, as a result, they form an unbreakable bond. It is a process wherein both of the protagonists gain invaluable insights and see improbable growth: they both experience a proper Bildung of one’s own, in the company of one another. For Nobody, this is a journey that restores his sense of self through his encounter with a ‘dead man’, a hapless accountant from Ohio with the name of a great English poet. Through the highs and lows of their journey in a treacherous landscape, a lone exile Native American learns to embrace a ‘fucking stupid white man’ as his dear friend. Whilst Nobody plays the part of a knowing guide to Blake, the solace and joy given by the friendship with Blake cannot be underestimated. As for his counterpart, Blake, by the guiding hand of Nobody, for the first time in his brief life, he realises the depth and extent of injustice upon which his country was founded; he begins to comprehend the nature of struggle between the colonialists and the colonised, precisely at one of the tipping points of history wherein one world comes into being, and another begins to vanish. The journey gradually opens his eyes to other Forms of Life, that is, various Native American cultures. At first, Blake responds to Nobody’s utterances with fear, puzzlement, bewilderment, and annoyance. Whilst his inability to fully comprehend or relate to other Forms of Life remains throughout their voyage, he develops an enduring respect toward this ‘strange man’ and his ‘kins’. His voyage with Nobody is transformative in every respect: At one point, Blake is given a chance to take a stand on his own. When a merchant-priest (Alfred Molina) refuses to sell tobacco to Nobody by claiming to have no stock, Blake steps in and exposes his lie and hypocrisy. As the priest realises who this stranger is, and attempts to shoot him for the bounty, Blake shoots and kills him. Then Nobody remarks: William Blake kills white men. And he concurs: Yes. William Blake kills white men. This is a far cry from the timid and neurotic accountant on board a steam train, hanging on to a piece of paper sent from the ‘town’ of Machine. He is ready to take a stand for his friend, and himself.

Remarkably, this friendship begins with an unthinkably basic misunderstanding: Nobody thinks that Blake is the celebrated English poet, William Blake. Blake, to his credit, flatly denies this from the very beginning, and he continues to insist that he is not a poet. In fact, as he candidly states, he has no literary background, and thus has no idea who his namesake is and why this strange Native American is raving about an English man. Despite Blake’s repeated denial, Nobody appears to unwaveringly believe an unemployed accountant from Ohio to be a visionary English poet, and decides to guide, accompany, and see his journey to the end. As for Blake, he cannot make sense of what his friend is getting at; despite his friendship, he remains a stranger to the worlds from which Nobody emerged. Despite the respect he develops, Blake cannot comprehend Native American Forms of Life. Blake also remains ignorant of high-culture; it was Nobody, captured by the English and educated in England, who shows him the potent possibility of poetry. Unfortunately, despite developing a limited, yet meaningful relation to a few verses of William Blake, Blake has no opportunity to further his learning: He is a fugitive with a remarkable price tag, in the process of dying from a fatal gun wound, and thus set to remain ignorant of high-art which Nobody learned to appreciate. Still, in Dead Man, the protagonists’ friendship is as genuine as a human relationship can be despite the persistent lack of understanding of one another. This is an affront to a widely accepted notion of friendship: a friend, as they say, is someone who understands you in a meaningful way. Whilst many might see the way Blake and Nobody bond as ‘superficial’, and thus being inclined to dismiss their friendship as a typical ‘Jarmuschian aesthetic pretence’ without giving it a second thought, I consider the way their friendship is made possible by Jarmusch to be both philosophically and practically significant. And thus, in what follows, I wish to discuss the way in which Jarmusch enables the friendship between his protagonists to be of critical importance for us.

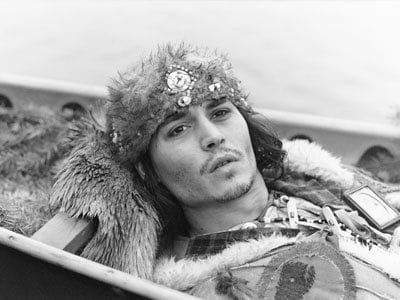

Perhaps one of the most outstanding characteristics of Jarmusch’s attitude toward the multiplicity of Forms of Life is his acute intercultural humility. Whilst Jarmusch is credited for sober representations of American ‘Frontier’, as well as Native American culture, he has no illusion that his is a perspective of a stranger to Native Americans; he is never going to claim ‘authenticity’ in his representation of their Forms of Life. Depp’s Blake is never going to learn to fully appreciate the ways of life which he encounters, despite their tremendous educational effects on his world-view. In this light, it is significant that Jarmusch did not provide translations to the lines spoken in a few Native American languages. The director has been consistently employing this ‘method’; in his debut feature, Stranger Than Paradise, Hungarian dialogues are not translated at all, and it was quite refreshing to experience the multiplicity of Forms of Life existing within a supposedly one Form of Life that is American culture. By providing no translation to non-English dialogues, Jarmusch is expressing his deep appreciation of the world wherein almost infinite variations of human existence, and its experience, can be observed if, and only if, one remains unassumingly open to such possibilities. In Dead Man, Jarmusch provides Native American dialogues in two distinct languages, including ‘in-jokes’, and they are solely aimed at the speakers of their languages. Whilst most American critics were not impressed, Jarmusch’s approach is consistent with his appreciation of the multiplicity of Forms of Life. By unfailingly employing this method, Jarmusch is essentially asking us: Why do you assume that one has to exclusively aim for an English-speaking audience? Why does everything have to be translated so that it is appropriated by the dominant cultures? It is a gesture that is at once rare and significant for our time, wherein countless languages, and Forms of Life, are denied its existence (To have a glimpse of the scale and depth of the cultural slaughter, please check following links: [http://www.linguistlist.org/forms/langs/get-extinct.cfmhttps://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/what-endangered-language(http://www.linguistlist.org/forms/langs/get-extinct.cfm,). And he does all of this with a refreshing understatement; he simply puts his belief in praxis, rather than preaching it. He let the human relations in the scenes speak for themselves, rather than enlightening the audience with smart and well-meaning lines. This is all due to his intercultural humility; he is absolutely clear that he, as a stranger, cannot transcend the distinctness of whatever Forms of life he encounters. Still, that is not to say that he cannot interact with, and even develop genuine friendship with, someone from other Forms of Life. These points are of great philosophical, and practical, significance. For Jarmusch, understanding based on linguistic communications is not an absolute prerequisite condition for a meaningful interpersonal relation to occur. Traditionally, Western philosophy places critical importance to conceptual clarity and explicitness which are only achieved by the ‘correct’ use of linguistic tools. Whilst Jarmusch never denies the importance of clear communications and the understanding it offers, by relaxing the attitude toward misunderstanding by seeing the humour and humanity in it, Jarmusch demonstrates a greater appreciation for the multiplicity of Forms of Life. For Jarmusch, misunderstanding can be a rich human experience, not to be reduced to linguistic ‘misfiring’ (J. L. Austin). From this specific viewpoint, misunderstanding is not always a deal-breaker that must be treated with contempt. In translation of an intricate piece of poetry or philosophical writing, one oft encounters words or concepts that cannot be translated into other languages fully. Instead of trying to appropriate or conquer alien thoughts by forcing an inadequate substitute, Jarmusch wants us to embrace ‘otherness’ as they are. Whilst such an attitude is not entirely novel, given our concern over conceptual clarity in philosophy, such a generosity exhibited by Jarmusch on human relations offers us a fresh perspective and possibly a beneficial turning point in rethinking how one relates to another. His approach on intercultural relation is also of great practical importance. As we, both individually and collectively, struggle to determine how to respond to ever greater contacts with the ‘Other’, Jarmusch’s respectful, humane, and relaxed attitude toward the ‘Other’, who are different from ‘us’ and cannot be fully assimilated, or absorbed, into a familiar Form of Life, can transform discussions surrounding our political struggle over domestic and foreign policies concerning ‘alien subjects’.

The benefit of Jarmuschian openness is not limited to intercultural relations; it can be equally applied to interpersonal relations. Jarmusch’s two protagonists, Nobody and Blake, despite the fundamental misunderstanding (Nobody) and the lack of comprehension (Blake) of one another, form an unbreakable friendship. By embracing the inevitable fallibility and misunderstanding in our interpersonal relations, one invites a possibility of forming a genuine friendship with someone whose thoughts and attitudes remain difficult to understand. In addition, in this particular case, one of the pair is not a native English speaker, and thus there is noticeable incompleteness in their conversations. Whilst one might wonder how this hindrance may affect their friendship, upon close viewing, one is struck by a revelation: Ultimately, the incompleteness does not matter at all. Interestingly, it is at the beginning of their friendship, that is, at the state when they are unsure of their companion, when there is a greater need for verbal communications. Confusions arise due to the lack of understanding, and they both have second thoughts about their respective partner. Yet, as their friendship deepens, the need for linguistic communication begins to lessen. Whilst this may be partially due to the increasingly weakened state of Blake, the looming death does not tell the whole story. There is a moment late in their journey to support my point. After reuniting with Nobody, upon hearing one of Nobody’s spiritual utterances, Blake looks at Nobody with great affection and spoke: You are a strange man. This statement marks a watershed moment in our understanding of possible human relations. Blake is embracing Nobody as his friend, despite everything about him that eludes his understanding. Such a relating is enabled by an implicit and intersubjective understanding about a person. It is critical for us to note that Blake’s appreciation of Nobody’s opaqueness is not informed by a subjective understanding; his embracement of Nobody is based on real interactions he has with Nobody, and thus it is neither pure imagination nor delusion. And yet, it is not a mere objective understanding; the totality of the facts which Blake knows about Nobody amounts to so little that exclusively relying on such information, however concrete and objective they may be, means reducing a person into a set of data. And thus, whilst Blake’s understanding of Nobody is incomplete, it is formed by real interactions between two agents. The fact that we can recognise the possibility for us to obtain such intersubjective understanding and develop a genuine friendship with a ‘strange person’ comes as a revelation. Once adopted, such an attitude invites a possibility for us to develop an open and more respectful friendship with persons from a wider range of Forms of Life, thereby contributing positively to the improvement of our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. In the end, one must realise that such a generosity is necessary for all interpersonal relations to occur. As I have elaborated in the article on Ex Machina, respectful acceptance of a certain opaqueness that denies our full access to the thoughts and feelings of another person is a prerequisite condition for a fair and meaningful relationship. In this sense, the concept of friendship that solely relies on clarity and explicitness in communication is mistaken. Jarmusch is correct in his embracement of interpersonal relations which are open to misunderstandings and lack of comprehension not only because of our inherent fallibility, but also due to the very nature of personal agency that requires a certain degree of impenetrability. And thus, despite the outward absurdity, Jarmusch’s representation of friendship is not only more open and generous, but also more precise.

The Paradise of Strangers

We have discussed ways in which Jarmusch refreshes our idea of how to build a genuine relationship and what the prerequisites for such a liaison are not to occur. Jarmusch shows us a greater potential for our capacity to relate by demonstrating his embracement of our fallibility through his protagonists, who forge an unbreakable bond despite Nobody’s complete misunderstanding about who Blake really is, and Blake’s inability to comprehend his friend’s world. Whilst clear communications, and understanding based on them, are generally helpful, according to Jarmusch, they are not necessary for a great friendship to begin and endure. This is because Jarmusch recognises the roles of non-linguistic elements in our relationship; we are far more susceptible to irrational and non-linguistic aspects of our experience. As we have seen in Dead Man, even the most clear and simple statement, such as Blake’s flat denial of being a poet, cannot always dispel misunderstandings. Humankind’s fallibility is such that one oft fails to adjust one’s view despite the overwhelming body of empirical evidence and/or the force of reasoning and arguments against it. And thus, it is safe to say that the friendship between Nobody and Blake is based on a certain mutual recognition that drew them together, and a shared experience of the journey that strengthens their bond. In order to determine what each of the protagonists recognised in the other, first one must examine each of their footsteps that define who they are.

Nobody, who contributed to Dead Man’s reputation as one of the very few cinemas which offer representations of Native Americans without relying on clichés, is a Native American person with an eventful past that shapes his painful present. He was captured by the British during their violent raid against his tribe when he was fairly young, and remained captive for a very long time. He was sent to Britain and exhibited as a caged ‘animal’, and paraded through the streets to satisfy the curiosity of spectators. Eventually, he was relieved from his cage, sent to a boarding school and educated as a ‘normal’ English pupil. Amid the pain of homesickness, discrimination, and isolation, he encountered the verses written by an English poet, William Blake. By his admission, he was so taken by Blake’s poetry that they became his life-line; he endured and survived the painful existence by reading and absorbing these ‘powerful words’. Eventually, he took his chance to escape from Britain, and returned to the land of his people. When he shared his account, however, nobody believed him; he was named Exaybachay, meaning ‘He who speaks loud, yet says nothing’. This is a painful form of excommunication that defines who he is for the rest of his life. For no fault of his own, he was forced to become an exile; neither the British nor his ‘fellow’ Natives accepted him as their own. Being alienated from both sides of the conflict, that is, advancing Anglo-European colonialists and diminishing Native Americans, he decides to live his exile by his own terms by rejecting the name he was given, Exaybachay, and adopts an English name: Nobody. Whilst his new name, in ‘enemy’s tongue’ no less, is an expression of defiance, it is also an acknowledgement of his new status: whether he likes it or not, he is now forced to live as a shadow. He no longer stands for either side of the conflict, despite his strong, at times passionate, disapproval of European colonists. As an excommunicated, Nobody is no longer able to take part in the Natives’ struggle against white colonists; he can only watch the inevitable as a non-entity. Despite his feelings and verdicts on who is in the wrong, Nobody has become a voyant; not unlike the author of Une Saison en Enfer, he is a bewildered, yet disinterested observant, who starkly follows the cruel fate: the destruction of what was formerly his Forms of Life and the rise of ‘civilisation’. He senses the sinister nature of the ‘new power’, yet is restricted to observing humanity’s self-destruction as it unfolds.

As for Blake, his life before the fateful journey was utterly unremarkable. A timid and neurotic accountant from Ohio is driven out of his comfort zone after the break-up with his fiancée to seek fortune elsewhere, only to realise when it is too late that he is on a one-way trip to ‘Hell’, that is, the American ‘Frontier’. He has received a letter from Dickinson Metal Works in the colonial outpost called ‘Machine’; it says that he is offered a position as an accountant. Despite the warning from the stoker (Crispin Glover) of the train, who predicts Blake’s demise and describes his final moments on water, he arrives at Machine due to a lack of means to reverse course; he bet everything on the prospective job, and he has no money left for the return train. Once arriving at Machine, Blake finds out that his post was taken by someone else. He tries to settle the matter directly with Mr. Dickinson, a despotic owner of the business (and the town), yet is quickly booted out of his office with a shot gun aiming at him. Distraught, Blake goes to the one and only bar and buys a drink. As he sits outside and downs alcohol, he sees a woman, Thel Russell (Mili Avital), being pushed out on the street and falls into the mud. Blake helps her and Thel asks him to walk her to her room. Thel is a quietly strong woman; she quit prostitution, the only job available for women in colonial outposts like Machine, and took up making paper flowers to sell, and dreams of pursuing a career as an artist. Chemistry soon turns into attraction, and the pair soon ends up in bed. When Thel’s former lover, Charlie Dickinson (Gabriel Byrne) visits her to declare his undying love for her, Thel stands firm. In despair, Charlie shoots at Blake, and Thel covers him and dies from the shot. Blake takes Thel’s gun and randomly shoots at Charlie in panic as Charlie silently awaits his death. Eventually, Blake shoots him dead, and discovers that the bullet pierced through Thel and fatally wounded him in his chest. Desperate, Blake steals horses and escapes into the night. It turns out that Charlie was a son of the boss, and Mr. Dickinson orders three bounty hunters, including the legendary Cole Wilson, to hunt down Blake. In short, Blake is forced to be in exile from a seemingly innocuous decision to accept a job offer, and with a cruel twist of fate, becomes an outlaw. And he becomes one in the country to where he is supposed to belong; for the first time in his life, Blake encounters the savageness of the colonial empire, and, shellshocked by his brief encounter with the dark underbelly of the nation, like Karl Roßman (Der Verschollene by Franz Kafka), he soberly realises that he has nowhere to go.

It is not difficult to see what made our protagonists from very different Forms of Life kindred spirits: they are both exiles in this brutal no-man’s land wherein money and bullets reign supreme. Despite obvious misunderstanding and incomprehension from both sides, the two of them realise that they are exactly alike: alienated, purged from Forms of Life, each of them has obtained a unique, and unobstructed, view on the state of affairs: a rising Form of Life of white colonialists is in the process of systematically degrading and annihilating other Forms of Life. As exiles, Blake and Nobody, coming from opposite directions, have found a space wherein they can look each other in the eyes and recognise one another as their counterpart, a companion, without the restrictive influences of whatever prejudices they might have had. And, interestingly, it is Nobody’s mistaken idea of Blake’s identity that plays the decisive role in overcoming the peril of killing off the possibility of mutual recognition; without this misunderstanding, Nobody might have left this ‘f- ing stupid white man’ to die. This probably comes as counterintuitive to most; without second thoughts, one might simply dismiss this turn of event as a typical Jarmuschian twist. As we have discussed, this is far from the truth; if one is receptive, it signifies the fundamental shift in our understanding of interpersonal, and intercultural, relationships. A Jarmuschian concept of friendship is considerably more expansive, and potentially more rewarding than a strictly linguistic concept of human relations. Yet, in order to begin the process of relating, one needs to be unassuming to whatever one might encounter, and Jarmusch, like David Bowie before him, thinks that one must enter into a certain space wherein one can maintain a great distance from all the Forms of Life one has become familiar with (To recount Bowie’s philosophical embracement of alienation, please read my articles in the section, The Promised Land in the page Shadow Play, and the articles in the section, Black Star in the page Silent Age). Whilst the forced exile from one’s own Form of Life as seen in Dead Man is an undoubtedly extreme proposition, it certainly highlights how a critical distance from one’s own Form of Life is necessary to allow a proper agency, and thereby enabling one to encounter another without a set of restriction to one’s understanding imposed by whatever Form of Life to which one thinks one is belonging. In this respect, Nobody has taken a significant step toward the path of voyant; instead of meekly accepting the forced condition of an exile, he rejects a given name, Exaybachay, and adopts an English name to define his mode of being in this world. Following his example, Blake eventually catches up with his friend; realising the powerful effect of verses written by his namesake, Blake opens himself up to the poetic and aesthetic aspects of the life on earth. And thus, in the end, the no-man’s land called the American ‘Frontier’ becomes the space where one can reinvent oneself, not merely lands to conquer and to impose one’s savage materialism. In this paradise of strangers, one can finally meet and develop mutual recognition as a pretext to develop a possible friendship. Whilst one might find such an individuality, the degree of autonomy and separateness, unwelcome, or even terrifying, it is a necessary path to consider if one ever dreams of developing a genuine relationship with another human being.

Conclusion

Whilst what Jarmusch achieved with the double-exposure of an American portrait with Cole Wilson is momentous in itself, if this is all that there is, Dead Man falls far short of what it is. It is a masterpiece of a rare kind, sardonically comic yet sincerely reflective, awkwardly self-conscious yet fearlessly objective and poetic, a unique feat which only Jarmusch can achieve. Dead Man is more than a deconstruction of America’s self-image; it offers a glimpse of what lies beyond the cultural blindfold represented by ‘Frontier Thesis’ through the fantastic voyage of two characters: Nobody and William Blake. And, as we have noted earlier, their journey together is of a rare kind; it is a philosophical journey which traces Blake and Nobody’s encounter with one another, their experiences of a Form of Life, that is, the savage Industrial Materialism of the 19th century, and the formation of a new perspective through their growing appreciation of one another. At first glance, it is all too easy to get lost with Jarmusch’s masterful storytelling and find his protagonists’ relations as an expression of typical Jarmuschian off-beat humour without realising its true significance. Yet, upon close inspection, it becomes clear that Jarmusch’s idea of a possible relationship and its implications are philosophically significant. In fact, it offers an important improvement to the Western conception of appropriate human relations, which considers correct understanding based on clear linguistic exchange as a necessary condition of meaningful relationship. By busting open this restriction, Jarmusch achieves a re-thinking of possible human relations.

As we have noted, Dead Man is a complex cinema with many nuances and layers to appreciate. Its significance is at once political, historical, and philosophical. It singlehandedly changes the view on America’s self-image, its historical origin, and its development. By having a clear and sober understanding of the historic context of the concepts that define how we see ourselves and how we think we should act, this must have a transformative effect on our daily lives. In this respect, the way Jarmusch shattered the self-image of America, which is entirely based on a narcissistic picture of the American ‘Frontier’, and replaced it with the representation of the savage reality of colonial outposts, is significant. In addition, Dead Man refreshes our concept of genuine human relations by pointing to the significant role of non-linguistic elements of our relating. Rather than imposing our preconceived concepts upon everything around us, Jarmusch prefers to allow the story to unfold on its own, thereby embracing misunderstandings, incomprehensions, amongst other human fallibilities. Jarmusch’s non-dogmatic approach to life and art is a gift for anyone who is willing to see the familiar with the eyes of strangers. In this age of uncompromising confrontations with rigid dogmatism and identity politics, Jarmusch’s non-pessimistic quietism allows the story to unfold on its own, rather than imposing one’s ideas and forcing a judgment that satisfies one’s need for a definite closure. It is a rare and precious example for us to consider; if we are successful in this endeavour, we might allow ourselves to entertain a hope to safeguard ourselves from the crippling paranoid and all-consuming hysteria of our time.