Days and Rays: Translating Kajii’s Stories

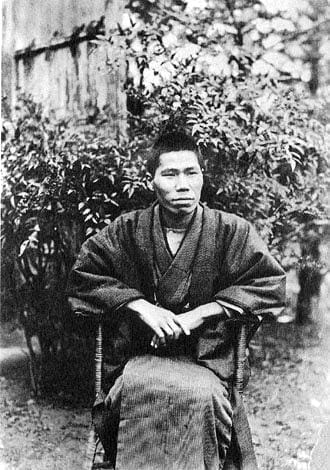

In the previous article, I have shared my profound respect for a little internationally known Japanese writer, Motojirō Kajii (1901-1932). Although he is recognised as one of the best prose writers in Japan, as far as I know, despite a few translations here and there, the body of his works is virtually unknown to the general readers internationally. Unless you read Japanese, French, Italian, Spanish, or Polish, you have very limited access to this singular author’s exceptional writing.

While I decided to take on the challenge of translating his works into English, I was well-aware of the difficulties this enterprise would entail. After all, along with Akutagawa, Kajii has been one of my favourite authors from Japan since middle school, and I used to purchase his collection whenever publishers refreshed the dust cover designs. These Japanese paperbacks fit comfortably in the pocket of a coat or a blazer, and I would carry his collection titled ‘Lemon’ and mused myself, imagining how Kajii would have wandered the street of pre-WWII Kyoto with an explosive fruit tucked in his pocket.

Still, an anticipation, however accurate, is just that: an anticipation. Whilst I do not deem Kajii’s prose impossible to translate into English (I do think, despite my admiration, it is impossible for me to translate Chyūya Nakahara’s poetry into English with any degree of satisfaction), it is far from a simple matter that suits artificially intelligent computational tools. In what follows, I wish to share some of the challenges with translating Kajii’s stories into English.

Days or Rays?

The Japanese language boasts one of the most complicated systems of writing. We borrowed Kanji from Chinese, a system of logographic letters that represent symbolic meaning as highly abstract pictures. After having found the Chinese system unsuitable for Japanese, we had invented two phonetic systems of writing: Hiragana and Katakana. Whilst phonetic systems are more or less straightforward, due to the way in which we have adopted Kanji, we have been burdened with additional complexities. Whilst Japanese decided to adopt Chinese pronunciations and the reading of their characters, we also decided to attach our own pronunciation to the character with the corresponding meaning. For example, the letter for ‘tree’ thus has two pronunciations, one Chinese and one Japanese. As the result, each Kanji character has more than one pronunciation. In addition, Chinese adopted by Japanese had multiple sources. We learned the pronunciations of a character from different dynasties, different dialects, and different kinds, such as the Chinese used in the imperial court, and the Chinese used for the Buddhist scriptures. Given the ad hoc manner in which we adopted the Chinese system of writing and reading, Japanese adoption of Kanji is neither systematic nor consistent.

Now, challenging that may be, it tells only half the story. Since Kanji characters are logographic, unlike alphabetic languages, it allows rich ambiguity: each character can represent multiple concepts without losing its coherence as a symbol. Naturally, great poets and writers have been exploiting this characteristic of the Japanese language skilfully since the Heian period. Kajii is no exception: we sometimes cannot even agree on the translation of a given title of a story. Let us look into one particularly striking case.

Arguably Kajii’s most matured work, Fuyu no Hi, was written when Kajii’s tuberculosis was advanced enough for him to anticipate his approaching end. The title is often translated as either ‘Winter Day’ or ‘Winter Days’. Technically speaking, both are correct: the Japanese word Hi carries multiple meanings, and ‘day’ and ‘days’ are probably the most common interpretations in this context. Since the Japanese word Hi does not explicitly determine whether the word designates singular or plural, grammatically speaking, both are correct. Yet, since the story encompasses multiple days around the Winter Solstice, at a glance, ‘Winter Days’ seems a better choice.

The Japanese word Hi also means ‘the Sun’ and ‘the Sun’s Ray’. If one pauses and ponders, one finds both meanings fit quite well as the title, if not better than ‘days’. In the end, I rejected all the aforementioned possibilities.

Does it mean ‘Winter Days’, ‘The Winter Sun’, or ‘The Ray of the Winter Sun’ are wrong translations? No. Kajii is exploiting the rich ambiguity of the Japanese language to its full effect in choosing this seemingly simple title for a story. Fuyu no Hi is at once ‘Winter Days’ and ‘The Winter Sun’ for a Japanese reader, without invoking any sense of contradiction or dilemma. The title holds all the evocative power due to the ambiguity that is natural to the Japanese language. The tension and dilemma exists only for an English translator, who needs to settle on one of many choices by discarding all other legitimate meanings conveyed by the author.

After some deliberation, I settled with ‘Winter Light’.

Kajii As An English Writer

At one level, the reason I decided on this title was the same reason others went with other options: the English language did not allow translators to recreate the same rich ambiguity with a single word, Hi. So long as one is going to translate Kajii into English, one must choose one nuance that one thinks is close to the author’s intention, the one that better represents the theme or the mood the story conveys.

There were two reasons why I rejected ‘days’ and ‘the Sun’. Whilst neither was incorrect, I wished to find a word to preserve as many nuances as Kajii trusted in a single word, Hi. Choosing one over another from the aforementioned options in this case meant that one could convey only one meaning of this Japanese word. This meant I needed to find another word to convey the rich meaning and the nuance of this word.

Hence, I went back to the text and tried to understand what was affecting our protagonist throughout the story to tease out the subjective meaning of Hi for Kajii’s alter ego. Eventually, I realised that the story was defined by three elements: the protagonist’s connection with his mother; his worsening illness; and the ways in which he was affected by the light, both natural and artificial, including its lack thereof.

Kajii’s writing is rich in imagery, and he expresses his thoughts and feelings through the observation of the inverted landscape: very much like with haiku poets, he observes the external world with a certain detachment, only to reveal his internal landscape. Not unlike Georg Trakl, Kajii’s visions assume the quality of dissociation, except that, for both, they are expressing the most intimate, inner thoughts and feelings as seemingly impersonal poetic imageries. This mode of writing, what I may call ‘Detached Immanence’, is far more authentic and sincere than any confessional mode of writing pretend it to be. In Kajii’s case, one might legitimately argue that ‘Cog Wheels’ and other writings by Akutagawa before his untimely death served as the model. Still, Akutagawa’s later writings drew from his canonical knowledge: the ominous symbols that haunted his world were as much about the decline of his world as the demise of the modern civilisation. As the stark lyricism of his prose suggests, Kajii’s mode of writing is closer to that of Trakl and haiku poets. The poetic infusion of the external and the internal in his writing means that translators need to pay close attention to every evocative description of the landscape. This understanding led me to seek the motif that ran through the entire story before determining the English title. And that motif was ‘light’.

The most prevalent theme of the story is the protagonist’s great sensitivity to the effect of the light, in particular, that of the winter sun. In one passage, the protagonist observes the shadows cast by pebbles, sensing the colossal existential melancholia in each and every one of them, as if they were Egyptian pyramids, the ancient monuments that have survived and witnessed the history of destruction. Kajii’s protagonist is affected by the slightest changes to the angle of the ray, as well as the subtle changes to the shadowgraph on the wall of a building he observes every day. He grieves the fact that he can only rise in the afternoon due to his physical decline, and has been reduced to looking out of the window only to observe the last of fading light, which crystallises the hopelessness of his struggles against the incurable disease.

Whilst this points to ‘Winter Sun’ as the best fit for the English title, it is not necessarily the sun, but the light dictates the protagonist’s landscape. It is the effect of the light, including its absence, that affects Kajii’s alter ego, not the sun itself. After all, the story ends with the protagonist’s vein attempt to find a vista with the magnificent setting sun: despite his best effort, it is always distant and hidden from him.

Furthermore, he is not only affected by the natural light; also by artificial ones, both in reality and in his vision. At one juncture, the protagonist stood in front of his lodging, and noted the next door with the closed storm shutter. The look on the worn out shutter triggers dissociation to the protagonist, and, in the moment of desperation, he sincerely wishes the electric light would turn on, as if a simple light bulb could save him from his inevitable demise.

After repeated close reading, it becomes clear that the story is not merely about the ‘days’ his alter ego lives through, nor the ‘sun’ or the ‘light’ itself. The underlying motif is the parallel between the dying of the light and his approaching death. Since the English word ‘light’ is within a legitimate range of interpretation of the Japanese word Hi, I am going to use ‘Winter Light’ as my translation of Fuyu no Hi.

Another reason I settled upon ‘Winter Light’ was aesthetic. Whilst ‘The Winter Rays and Shadows’ would be more descriptively accurate, it does not agree with Kajii’s style: he prefers simple, evocative phrasing without exception. If one is concerned about the clear representation of the motif of the story, how about ‘The Dying Sun’ or ‘The Dying Days’? Either of them simply won’t do. Firstly, it is too far from the original title. Secondly, it is far too explicit for Kajii’s style. The power of his prose lies in the evocation through rich imagery conveyed by simple phrasing of lyrical austerity. Once the translation begins to explain the original, one must discard the undertaking and begin from the scratch. This is true for any writers, but especially so for Kajii.

In the end, in the world of literary translation, accuracy is necessary but not sufficient. To produce a satisfying literary translation, one must imagine a writer as if she/they/he is a native of the target language. In this case, much of my struggle revolves around imagining Kajii as an English writer and trying to understand what phrasing and word choices he would have made.

In the next article, I am going to reflect on his style and the challenges posed by it.