The Conformist (1970)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s seventh feature film, The Conformist, was released right at the heel of Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (Götterdämmarung) (1969). Both movies explore Europe’s darkest moment; whilst Visconti dealt with the creeping process by which Nazism took hold of German society, Bertolucci chose to confront his own country’s skeleton in the closet by adopting Alberto Moravia’s novel of the same title. Both directors expressed their anti-Fascist politics in their respective works, yet Bertolucci’s work is all the more powerful for reasons which I wish to discuss here.

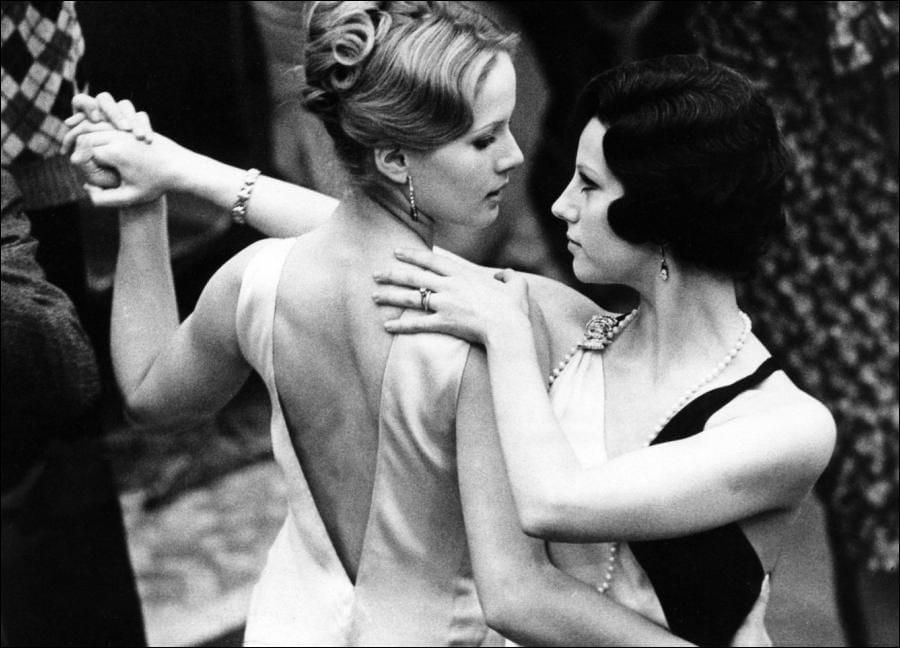

The Conformist tells the story of a young bureaucrat, Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant). He volunteers for the Fascist secret police to spy on his former professor, Luca Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), who is exiled in Paris due to his strong opposition to Fascism. Marcello’s reason for collaborating with the secret police is not out of his support for Fascism, not his fear for personal safety, or his career ambition; it is that he wanted to acquire a sense of normalcy for himself. This desire to assume the appearance of normalcy is the guiding force of his life; it is also the reason why Marcello marries Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), a daughter of petit-bourgeois. Marcello’s proposition was to use his honeymoon to Paris as a cover, approach Quadri, and collect information on anti-Fascist activities in Italy. However, the secret police abruptly alters the once-approved plan of Marcello’s and orders him to assassinate his former mentor. To add more complications, upon meeting his target in Paris, Marcello falls in love with Anna (Dominique Sanda), the mysterious wife of Quadri.

There are many great movies about Fascism and Nazism: from The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970) and Tin-Drum (1979) to Downfall (2004) and Hannah Arendt (2012). European cinema continues to reflect upon the political movements that swept the globe into furious and irreparable self-destruction. Despite the sheer amount of work and effort expended by post-war European cinema, The Conformist secures its stand-out status; it offers a unique character study of a conformist, and Bertolucci improves upon the original novel with his deep understanding of the subject. Unlike Moravia’s novel, which represents Marcello as a psychopath in his childhood, Bertolucci portrays Marcello as an 'everyman': a hopelessly mediocre man who wants to be and behave like others. This characterisation of a conformist is one of the best cinematic representations of what Hannah Arendt called the Banality of Evil. Like Adolf Eichmann, Marcello commits abominable crimes not because of ideology, but because of his desire to conform to the system. This film makes a great supportive argument for Arendt: it is not a crazy maniac who is truly dangerous, for such a maniac cannot accomplish great evil on his/her own. It is 'ordinary' people like Eichmann and Marcello who are truly dangerous, for their ruthless complicity with the powers-that-be.

The problem with people like Marcello is: Once you make a pact with the Devil, the complicity cannot be partial. This is precisely the point made in The Damned by Visconti. You cannot just commit one crime and wash your hands, as there is no walking away from the Devil. Visconti’s insight is indeed illuminating, yet Bertolucci went even further with this film. Visconti still locates evil as external to the main protagonists of The Damned, whilst Bertolucci locates the source of evil within an ordinary person. It is not some powerful and devilish person or an organisation manipulating people to do evil; the evil lurks in our quite ordinary desire to be normal and accepted as such by society. This conformity may appear quite innocent in a time of peace. However, as Nietzsche observed aptly, it turns us into the 'Last Man', the tool of whatever institution to which we think we belong. Bertolucci’s rendition of Marcello perfectly demonstrates this point. And yet, his brilliance does not end here. He also exposes the impossibility of a conformist agenda by showing how Marcello’s desire to acquire normalcy in his life alienates him from humanity, and turns him into a monster, albeit a quite petty one. The more he tries to become normal, the more isolated and grotesque he becomes. Marcello does not realise that his very pursuit of normalcy prevents him from acquiring it. After all, 'normal' people to whom Marcello wants to belong do not even think about pursuing ordinariness; normal life is simply the given, something that people just do. Like breathing, it is not the subject of thought, and they do not know any other way to live.

This heightened self-consciousness about one’s alienation and intense desire to overcome it, however, are not unique to Marcello. It is symptomatic of the spirit of his generation. The people, dead or alive, who became prominent in the 1920s and 1930s shared a certain sense of doom. They were disgusted by a decadent, corrupt European civilisation in its decline. However, for many of them, this sense of doom was also accompanied by a feeling of liberation from the past. Modern science and industry made many a European, such as Futurist, Positivist, Fascist, and Marxist, confident of their power as sovereigns of the universe, even though still many, like Kafka and Austrian poet Georg Trakl, saw this 'progress' as further evidence of Europe’s decline. Therefore, this generation, whilst confronting the authority of the past generation who represent this 'sick' civilisation, had not yet established their own cultural and spiritual identity. As they were suspended between the past which they rejected and the future which was still undefined, they experienced a deep sense of alienation from the world and from themselves. They could not tell themselves who they really were, and the mark of this dire distress is evident in virtually all of their representative work: the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Walter Benjamin, the writings of Kafka and Stanisław Witkiewicz, and the poetry of Trakl, to name just a few.

Despite the dire confusion this generation experienced, and the diversity of their response to it, there are a few things that were common to them. Firstly, there was a fervent desire to overcome the 'sick' civilisation of 'old Europe'. Some desired to conquer it by hastening its end with the brute force of revolution. Whether their chosen type of revolution was a political, scientific, or an industrial one, they all chanted one slogan in unison: Progress! Others resisted these radical solutions; they find the notion of progress of humankind dubious, and guarded themselves against it. Still, they shared with these revolutionaries the same desire to overcome the sick Europe of old, and confronted their parents’ generation in each his/her own complicated way. This radical break from the past characterises everything from this era; new physics, new art, new philosophy, and new politics. Yet, this sense of liberation from the past also invited moral ambiguity; things that were forbidden in the past suddenly became quite permissible. Both political far-right and far-left believed that everything, even murder, was permitted in the name of revolution and political correctness. And, given their desire to prevail over their parents, this premise offered them justification to take revenge on their 'guardians'. Therefore, Marcello’s complicity with Fascists can be interpreted as his way to get back at his parents’ generation. Fascist Italy merely presented an opportunity for him to exact his personal revenge. This explains why Marcello, a cowardly conformist, actively offered his service to Fascism. Whilst he could have been quite normal without his collaboration with the Fascist secret police, he simply could not pass on a chance to exact his revenge against his former mentor, Quadri, the 'father' who abandoned him by escaping the fangs of Fascists to a foreign land.

Secondly, this desire to making a break from the past and the resulting confrontation with their parents was often expressed in the area of sexuality. Again, the ways in which this generation reacted to the 'old Europe' in this sphere are diverse; some experimented with non-traditional sexuality in order to challenge established norms, whilst others repressed their sexuality in order to fight against the perceived decadence of their parents’ generation. For example, Berlin, before the Nazi takeover of Germany, was known to be the most liberal city in the entirety of Europe, both politically and sexually. As Fascist regimes actively and brutally prosecuted homosexuals, there was certainly an aspect of struggle over Europe’s sexual identity in this period of European history. Marcello’s fear of female sexuality is expressed by his disgust for his mother, and his feeling threatened by Anna’s attraction to Giulia. At the same time, Marcello himself is struggling with his past homosexual experience, and this episode is one of the reasons why he seeks the appearance of normalcy. Whilst it is not clear whether Marcello was homosexual or not, his fear of sexuality, despite his conquests, is evident: his sexual conquest was merely a way to conform to the societal norms. He does what he is expected to do, and nothing else. Anna is perhaps his only hope for overcoming his fear; she is the only person who could inspire raw emotion and confusion in him so that he can pursue life with absolute and complete surrender. Yet, he abandons her in the cold when it matters the most, not because of his ruthlessness, but of his cowardice.

Yet, most significantly, The Conformist is not a mere reflection of the past. Bertolucci was clearly finding many Marcellos amongst his contemporaries when he directed it. Whilst Moravia’s novel leaves Marcello dead, and thus closes this chapter of history, Bertolucci does not kill his protagonist: Marcello lives on as an ordinary citizen of the post-war Italy. This alternation is not merely to point out that there are many Fascists and conformists surviving as citizens of the republic. The point made by this film is that Italy was, and still is, not out of the shadow of its Fascist past. Tragically, he was proved right when a fellow Italian cineast, Pier Paolo Pasolini, was brutally murdered near Rome in 1975 for his leftist political view. And, sadly, Bertolucci’s message is still relevant today. Its relevance is not limited within Italy: it is universal. As we live in an age wherein the check and balance of power is quietly yet swiftly being eroded, transparency and accountability are blatantly discarded, and populism sways the masses, there are plenty of ideologies, be they religious, political, or cultural, that demand our absolute complicity. Whether this violation of human integrity might be demanded in the name of faith or patriotism, we must prepare ourselves for the trials that test the full strength of our persons. In this light, the importance of The Conformist cannot be stressed enough today. We must look out for Marcello, not only amongst us, but within us.